Les oscillations botaniques de Marc Buchy

Published online

Contributors

Marc Buchy

Marie Cantos

Clelia Coussonnet

Gil Ferrand

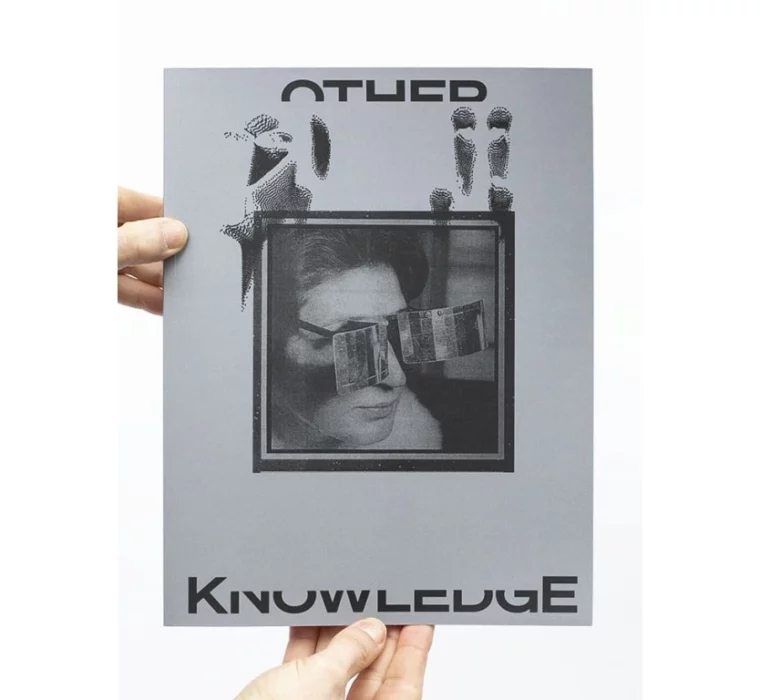

I was invited to contribute a text to Marc Buchy’s new piece in the framework of the program Mondes Nouveaux in 2023. My essay Les oscillations botaniques de Marc Buchy analysed organic temporalities, folklore and embedded knowledge, the impact of colonial circulation of plants, the political symbolism of plants, as well as the modern curse of running after time.

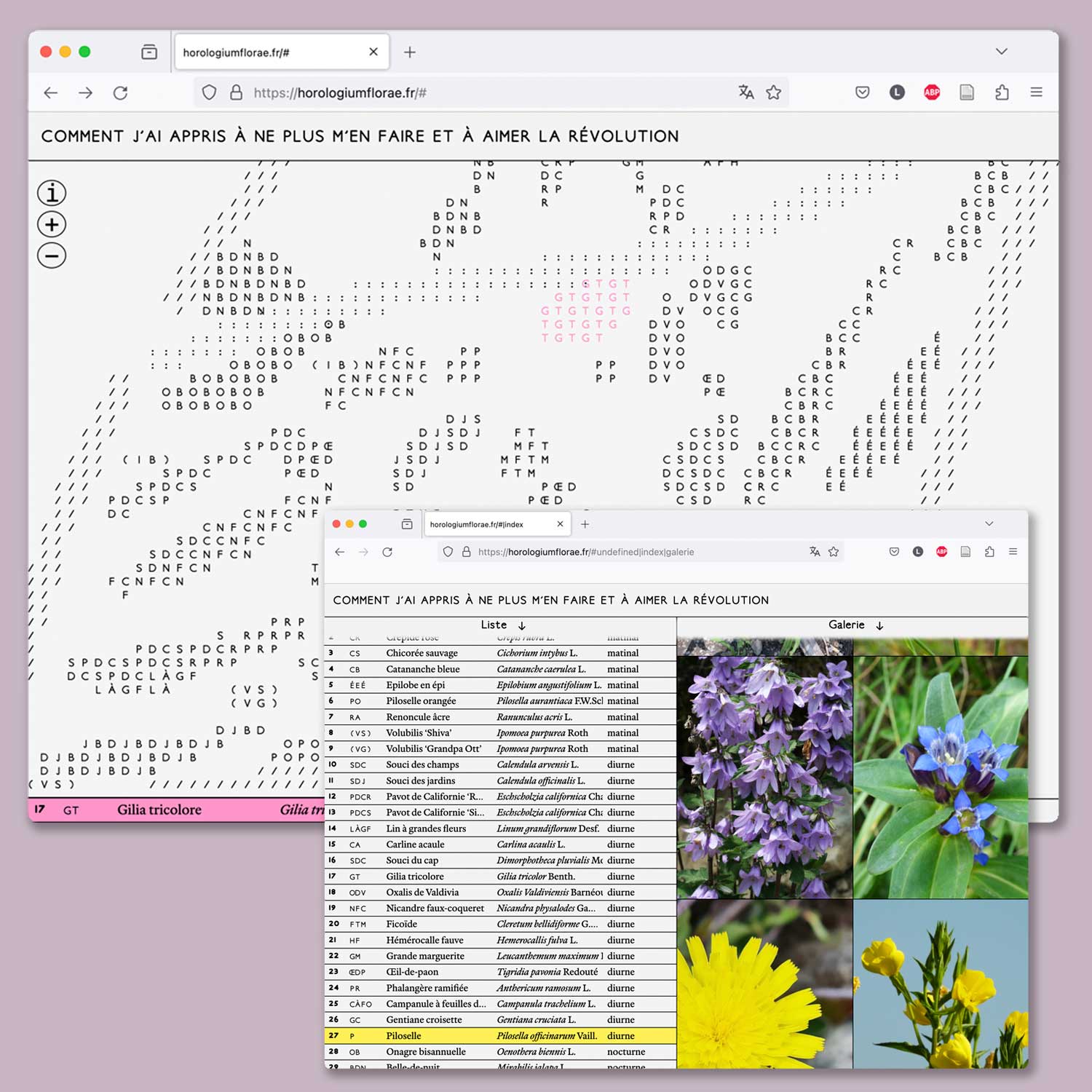

The full article can be read online on the beautiful website designed for the installation. The online interface features contributions by the artist, myself and Marie Cantos and Gil Ferrand, a botanist who also documented every single plant (photographing it and sharing witty descriptions of them). The website also includes a map of the planted species.

Les oscillations botaniques de Marc Buchy

Published online

Contributors

Marc Buchy

Marie Cantos

Clelia Coussonnet

Gil Ferrand

I was invited to contribute a text to Marc Buchy’s new piece in the framework of the program Mondes Nouveaux in 2023. My essay Les oscillations botaniques de Marc Buchy analysed organic temporalities, folklore and embedded knowledge, the impact of colonial circulation of plants, the political symbolism of plants, as well as the modern curse of running after time.

The full article can be read online on the beautiful website designed for the installation. The online interface features contributions by the artist, myself and Marie Cantos and Gil Ferrand, a botanist who also documented every single plant (photographing it and sharing witty descriptions of them). The website also includes a map of the planted species.

‘The cyclical alternations at work in ecosystems punctuated the passage of time, subtly linking bodies to their living spaces and to non-human living entities. Folklore, with its rituals, songs and other creative forms, combined human well-being with literal or imagined interaction with plants, the basis of a way of forming community.’

‘The cyclical alternations at work in ecosystems punctuated the passage of time, subtly linking bodies to their living spaces and to non-human living entities. Folklore, with its rituals, songs and other creative forms, combined human well-being with literal or imagined interaction with plants, the basis of a way of forming community.’

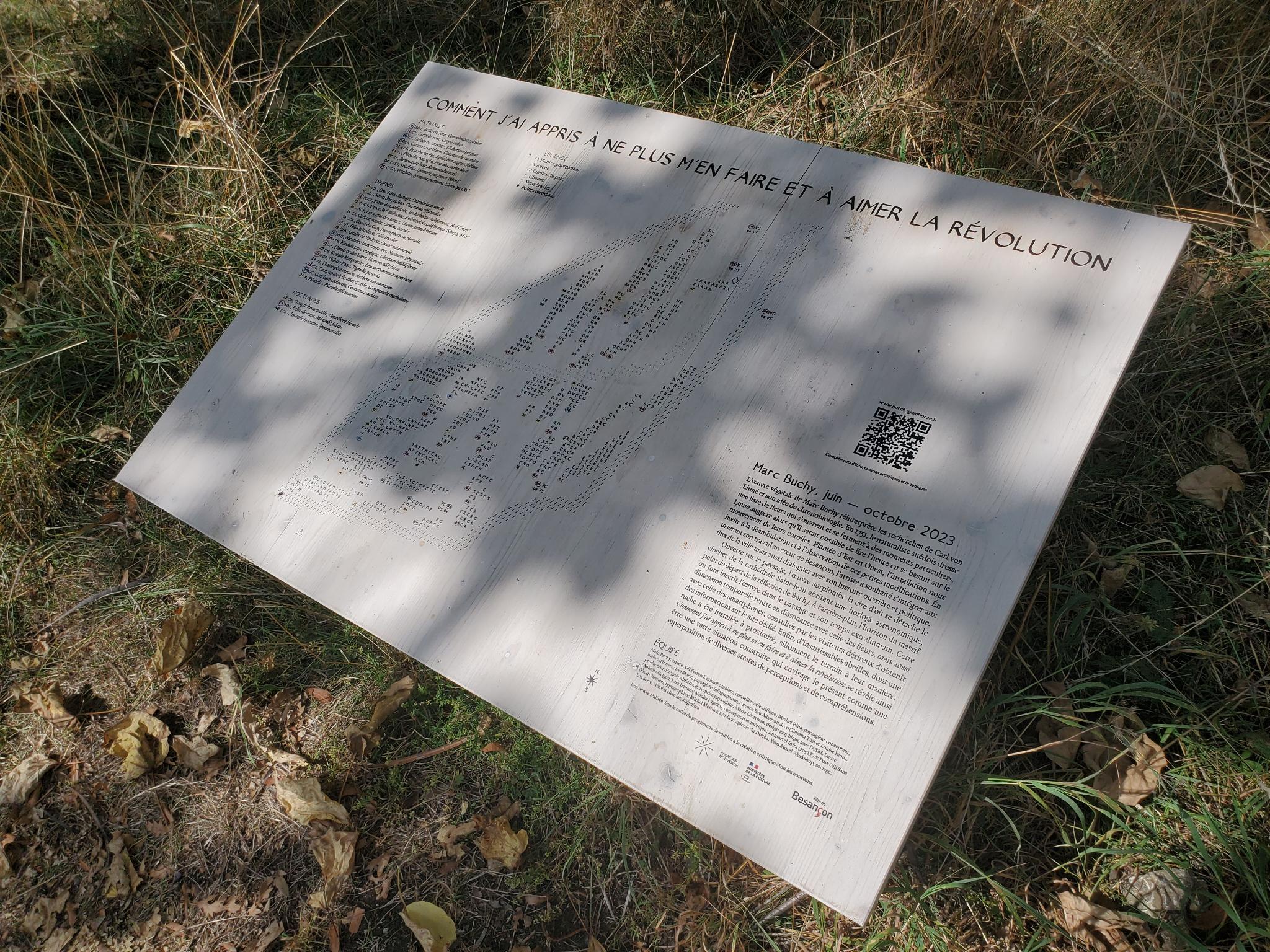

About Marc Buchy’s piece ‘Comment j’ai appris à ne plus m’en faire et à aimer la révolution (How I learned not to worry and to love the revolution)

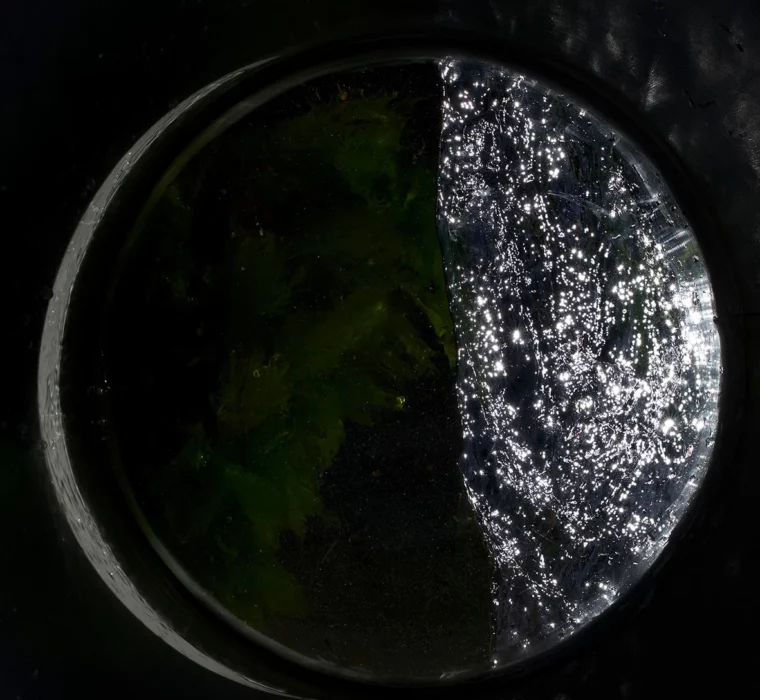

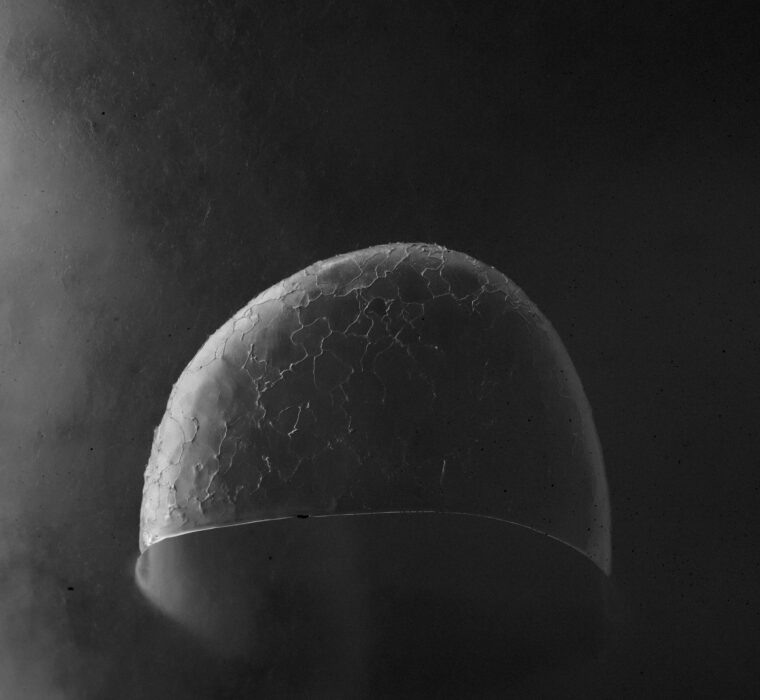

Marc Buchy’s plant work reinterprets the research of Carl von Linné and his idea of chronobiology. In 1751, the Swedish naturalist drew up a list of flowers that open and close at particular times. Linné suggested that it would be possible to tell the time based on the movement of their corollas. Planted from east to west, the installation invites us to wander around and observe these small changes. By placing his work in the heart of Besançon, the artist wanted to be part of the city’s flow, but also to engage with its working-class and political history.

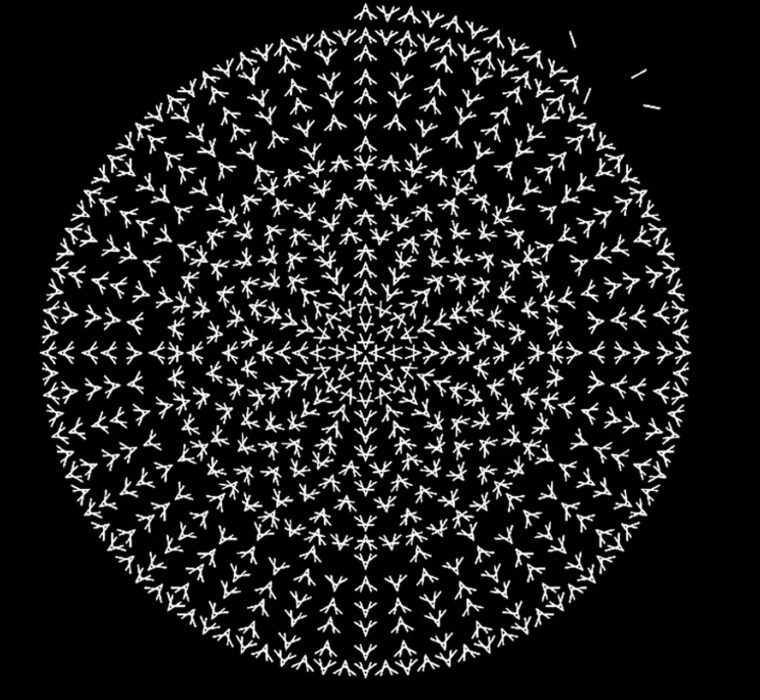

Open to the landscape, the work overlooks the city, with the steeple of Saint-Jean cathedral, home to an astronomical clock, the starting point for Buchy’s reflection, standing out. In the background, the horizon of the Jura massif sets the work in the landscape and its extra-human time. This temporal dimension clashes with that of the flowers, but also with that of the smartphones consulted by visitors seeking information on the dedicated website. Finally, elusive bees, whose hive has been set up nearby, criss-cross the grounds in their own way. Comment j’ai appris à ne plus m’en faire et à aimer la révolution is a vastly constructed situation that sees the present as a superimposition of different layers of perception and understanding.’

Info

Design by Marie Lécrivain, with ASBL Luuse (Antoine Gelgon, Lara Dautun, Natalia Pageau); Immortel Infra (205TF) & Post Gill Sans (Ésad•Valence), typography

Summer-Autumn 2023, French

Website with texts, photographs and descriptions of the plants, map of the planted species

About Marc Buchy’s piece ‘Comment j’ai appris à ne plus m’en faire et à aimer la révolution (How I learned not to worry and to love the revolution)

Marc Buchy’s plant work reinterprets the research of Carl von Linné and his idea of chronobiology. In 1751, the Swedish naturalist drew up a list of flowers that open and close at particular times. Linné suggested that it would be possible to tell the time based on the movement of their corollas. Planted from east to west, the installation invites us to wander around and observe these small changes. By placing his work in the heart of Besançon, the artist wanted to be part of the city’s flow, but also to engage with its working-class and political history.

Open to the landscape, the work overlooks the city, with the steeple of Saint-Jean cathedral, home to an astronomical clock, the starting point for Buchy’s reflection, standing out. In the background, the horizon of the Jura massif sets the work in the landscape and its extra-human time. This temporal dimension clashes with that of the flowers, but also with that of the smartphones consulted by visitors seeking information on the dedicated website. Finally, elusive bees, whose hive has been set up nearby, criss-cross the grounds in their own way. Comment j’ai appris à ne plus m’en faire et à aimer la révolution is a vastly constructed situation that sees the present as a superimposition of different layers of perception and understanding.’

Info

Design by Marie Lécrivain, with ASBL Luuse (Antoine Gelgon, Lara Dautun, Natalia Pageau); Immortel Infra (205TF) & Post Gill Sans (Ésad•Valence), typography

Summer-Autumn 2023, French

Website with texts, photographs and descriptions of the plants, map of the planted species

‘The title of Buchy’s work might suggest the political use of floral symbolism. From national emblems (cedar of Lebanon, Irish shamrock, Canadian maple) or partisan ones (royalist lily, socialist rose, ecologist sunflower), to revolutions with flowery names (roses in Georgia, tulips in Kyrgyzstan or carnations in Portugal) and the commemorative use of flowers (the red rosehip of May Day, although the less politicised lily of the valley has replaced it, or the poppy of the First World War), the examples are numerous. This is all the more interesting in the context of Besançon, whose history of labour struggle culminated in the strikes at the Lip watch factory in the 1970s.’

— Quotes by Clelia Coussonnet, Les oscillations botaniques de Marc Buchy, 2023

‘The title of Buchy’s work might suggest the political use of floral symbolism. From national emblems (cedar of Lebanon, Irish shamrock, Canadian maple) or partisan ones (royalist lily, socialist rose, ecologist sunflower), to revolutions with flowery names (roses in Georgia, tulips in Kyrgyzstan or carnations in Portugal) and the commemorative use of flowers (the red rosehip of May Day, although the less politicised lily of the valley has replaced it, or the poppy of the First World War), the examples are numerous. This is all the more interesting in the context of Besançon, whose history of labour struggle culminated in the strikes at the Lip watch factory in the 1970s.’

— Quotes by Clelia Coussonnet, Les oscillations botaniques de Marc Buchy, 2023