Spoiled Waters Spilled

Artists

Minia Biabiany

Marjolijn Dijkman & Toril Johannessen

Marianne Fahmy

Valentina Karga

Jessika Khazrik for The Society of False Witnesses

Anouk Kruithof

Rikke Luther

Elvia Teotski

With texts by

Atlas de la France Toxique

René Char

Daisy Lafarge

Lisa Robertson

Co-curated with Inga Lāce

In the framework of Les Parallèles du Sud Manifesta 13 Marseilles

Spoiled Waters Spilled

Artists

Minia Biabiany

Marjolijn Dijkman & Toril Johannessen

Marianne Fahmy

Valentina Karga

Jessika Khazrik for The Society of False Witnesses

Anouk Kruithof

Rikke Luther

Elvia Teotski

With texts by

Atlas de la France Toxique

René Char

Daisy Lafarge

Lisa Robertson

Co-curated with Inga Lāce

In the framework of Les Parallèles du Sud Manifesta 13 Marseilles

Spoiled Waters Spilled observes the organic circulation of flowing substances such as water and air, which exceed states’ borders while being slowly and often spectacularly poisoned at the local level by human activity. Bringing together artists addressing issues related to toxicity, circulation and water (and rivers in particular) in Marseilles and beyond, some of whom also engage with activism and protest, the project considers how industrial, agricultural and domestic pollutants disrupt the ‘postcard-dream’ image used by cities to promote themselves. The environmental reality of such cities is often quite the reverse: one of degraded rivers, soils, sediments and waters where bodies of all kinds are contaminated.

Spoiled Waters Spilled observes the organic circulation of flowing substances such as water and air, which exceed states’ borders while being slowly and often spectacularly poisoned at the local level by human activity. Bringing together artists addressing issues related to toxicity, circulation and water (and rivers in particular) in Marseilles and beyond, some of whom also engage with activism and protest, the project considers how industrial, agricultural and domestic pollutants disrupt the ‘postcard-dream’ image used by cities to promote themselves. The environmental reality of such cities is often quite the reverse: one of degraded rivers, soils, sediments and waters where bodies of all kinds are contaminated.

The multiplication of landfill sites continues – some open-air, many unauthorized, in both urban zones and nature reserves – and a lack of hazardous waste management persists at local, national and global levels. Whether the poisoning is obvious to us or not, the planet’s biodiversity is being strongly adversely affected, and the need for environmental rehabilitation has become pressing. When they are not actively camouflaging the persistent effects of contaminants on health and the environment, national governments, so often characterized by their collusion with corporations, tend to simply turn a blind eye to the situation. Yet residues of the pollution embedded in the current capitalist system continue to percolate, travelling with air particles, in river currents, and through our own veins. As we consider how to decontaminate bodies and ecosystems, the specters of ecological collapse, viral infection and – as we have seen recently – pandemic are more present than ever. Can we be inured to toxicity as an unavoidable fact? Or must we unite in an effort to fight back against it?

The exhibition also aims to explore the growing tension between the need for transnational responses to anthropogenic climate change and the enforcement by some nation states of ever stricter border policies, which serve to exclude ‘others’ and often further externalize ecological problems. Rather than opting for environmental protection measures, governments often insist on demarcation, obliquely fomenting fear while denying the reality of the circulation of harmful substances, as if toxicity could be forced to recognize state borders. The entanglement of borders and material circulation is addressed by Elisabeth A. Povinelli in her writing on the toxic destruction created by late liberalism. The places and powers that have been historically responsible for the colonial extraction of resources remain inevitably linked to the sites of extraction. “Europe, and by extension the US, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, etc., built itself from externalizing its expansion into and onto the bodies of others. It ate up and shat out others elsewhere than it claimed to be. The Congo was not in the Congo but in the shiny streets of Brussels,” she argues1. The interconnectedness of the world across many levels – from the ecological to the economic, the political and the social – has also become starkly visible during the recent pandemic.

1 Horizons and Frontiers, Late Liberal Territoriality, and Toxic Habitats

The multiplication of landfill sites continues – some open-air, many unauthorized, in both urban zones and nature reserves – and a lack of hazardous waste management persists at local, national and global levels. Whether the poisoning is obvious to us or not, the planet’s biodiversity is being strongly adversely affected, and the need for environmental rehabilitation has become pressing. When they are not actively camouflaging the persistent effects of contaminants on health and the environment, national governments, so often characterized by their collusion with corporations, tend to simply turn a blind eye to the situation. Yet residues of the pollution embedded in the current capitalist system continue to percolate, travelling with air particles, in river currents, and through our own veins. As we consider how to decontaminate bodies and ecosystems, the specters of ecological collapse, viral infection and – as we have seen recently – pandemic are more present than ever. Can we be inured to toxicity as an unavoidable fact? Or must we unite in an effort to fight back against it?

The exhibition also aims to explore the growing tension between the need for transnational responses to anthropogenic climate change and the enforcement by some nation states of ever stricter border policies, which serve to exclude ‘others’ and often further externalize ecological problems. Rather than opting for environmental protection measures, governments often insist on demarcation, obliquely fomenting fear while denying the reality of the circulation of harmful substances, as if toxicity could be forced to recognize state borders. The entanglement of borders and material circulation is addressed by Elisabeth A. Povinelli in her writing on the toxic destruction created by late liberalism. The places and powers that have been historically responsible for the colonial extraction of resources remain inevitably linked to the sites of extraction. “Europe, and by extension the US, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, etc., built itself from externalizing its expansion into and onto the bodies of others. It ate up and shat out others elsewhere than it claimed to be. The Congo was not in the Congo but in the shiny streets of Brussels,” she argues1. The interconnectedness of the world across many levels – from the ecological to the economic, the political and the social – has also become starkly visible during the recent pandemic.

1 Horizons and Frontiers, Late Liberal Territoriality, and Toxic Habitats

Marseilles, with its particular geography, port infrastructure and crowded beaches, has long had difficulties with water pollution. Its coastline was recently named among the most plastic-polluted in the Mediterranean. Sources of contamination include the port, the excess of cruise ships transiting through the city’s waters, and the presence of heavy industry. There are oil refineries and petrochemical plants, particularly at the Étang de Berre, as well the Gardanne alumina production plant, which discards toxic red sludge into the sea within the boundaries of the Calanques National Park. The river of Marseilles, l’Huveaune, which flows through the park of the Ballet National de Marseille, has also been severely polluted in recent decades.

Marseilles, with its particular geography, port infrastructure and crowded beaches, has long had difficulties with water pollution. Its coastline was recently named among the most plastic-polluted in the Mediterranean. Sources of contamination include the port, the excess of cruise ships transiting through the city’s waters, and the presence of heavy industry. There are oil refineries and petrochemical plants, particularly at the Étang de Berre, as well the Gardanne alumina production plant, which discards toxic red sludge into the sea within the boundaries of the Calanques National Park. The river of Marseilles, l’Huveaune, which flows through the park of the Ballet National de Marseille, has also been severely polluted in recent decades.

From left to right:

Opening/Exhibition views Spoiled Waters Spilled, Manifesta 13 Parallèles du Sud, Ballet National de Marseille, 2020 © Collectif VOST

Elvia Teotski, des canyons refermés, les collines se forment, 2020. Courtesy of the artist © Jeanchristophe Lett

Elvia Teotski, des canyons refermés, les collines se forment suite et cristallisation

Exhibition/Opening views Spoiled Waters Spilled, Manifesta 13 Parallèles du Sud, Ballet National de Marseille, 2020 © Jeanchristophe Lett/Collectif VOST

Valentina Karga, Manifestation, 2020. Courtesy of the artist © Jeanchristophe Lett

Exhibition/Opening views Spoiled Waters Spilled, Manifesta 13 Parallèles du Sud, Ballet National de Marseille, 2020 © Jeanchristophe Lett/Collectif VOST

Minia Biabiany, Spelling, 2016. / Marianne Fahmy, Magic Carpet Land, 2020. Courtesy of the artist © Jeanchristophe Lett

From left to right:

Opening/Exhibition views Spoiled Waters Spilled, Manifesta 13 Parallèles du Sud, Ballet National de Marseille, 2020 © Collectif VOST

Elvia Teotski, des canyons refermés, les collines se forment, 2020. Courtesy of the artist © Jeanchristophe Lett

Elvia Teotski, des canyons refermés, les collines se forment suite et cristallisation

Exhibition/Opening views Spoiled Waters Spilled, Manifesta 13 Parallèles du Sud, Ballet National de Marseille, 2020 © Jeanchristophe Lett/Collectif VOST

Valentina Karga, Manifestation, 2020. Courtesy of the artist © Jeanchristophe Lett

Exhibition/Opening views Spoiled Waters Spilled, Manifesta 13 Parallèles du Sud, Ballet National de Marseille, 2020 © Jeanchristophe Lett/Collectif VOST

Minia Biabiany, Spelling, 2016. / Marianne Fahmy, Magic Carpet Land, 2020. Courtesy of the artist © Jeanchristophe Lett

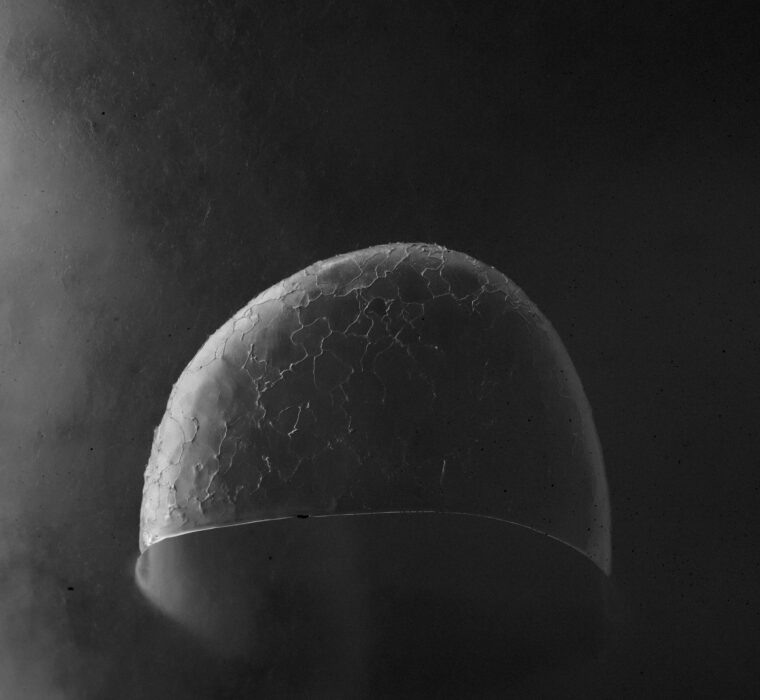

Elvia Teotski addresses ecological vulnerability and toxic imprints in the region of Marseilles. Collecting and sampling substrates, deposits, particulate water, she examines invisible yet hazardous pollution and the impossibility of upcycling it. Minia Biabiany brings another localized scandal to the fore, focusing on chlordecone, an insecticide with severe polluting effects on land, phreatic tables, the food chain and bodies that was widely applied in banana fields in Guadeloupe and Martinique between the 1970s and 1993. This case, as well as the pollution of Marseilles, are scrutinized in posters printed from the book Atlas de la France Toxique, a compilation of maps of different types of pollution in France made by the environmental association Robin des Bois. As early as 1946, the poet René Char raised his voice against the contamination of waterways in Provence with his theatre play Le Soleil des eaux. Spectacle pour une toile de pêcheurs. As for Lisa Robertson’s poem Rivers, it connects the many bodies that share riverine environments, exposing their collective vulnerability to toxins, hormones and desire.

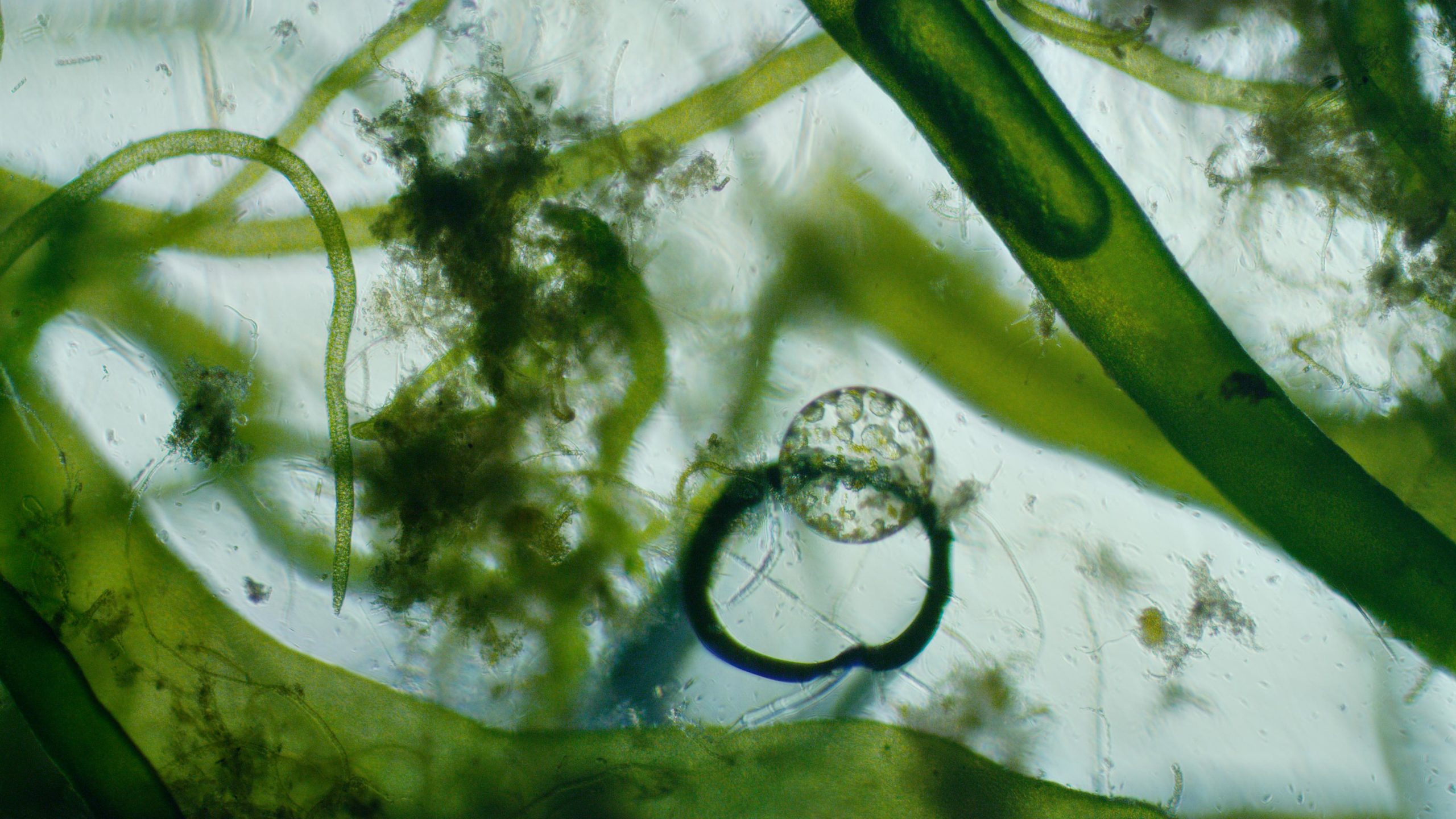

In reaction to the release of sewage into waterways by factories such as those involved in the textile industry, Valentina Karga works with natural dyes, emphasizing the importance of alternatives to toxic production processes that in their current form infect the environment. Marjolijn Dijkman & Toril Johannessen make us further aware of the effects of climate change by filming microorganisms, through a microscope, in samples of brackish water taken from the inner Oslo Fjord, where traces of human activity can be seen in altered saline and sea levels, among other phenomena.

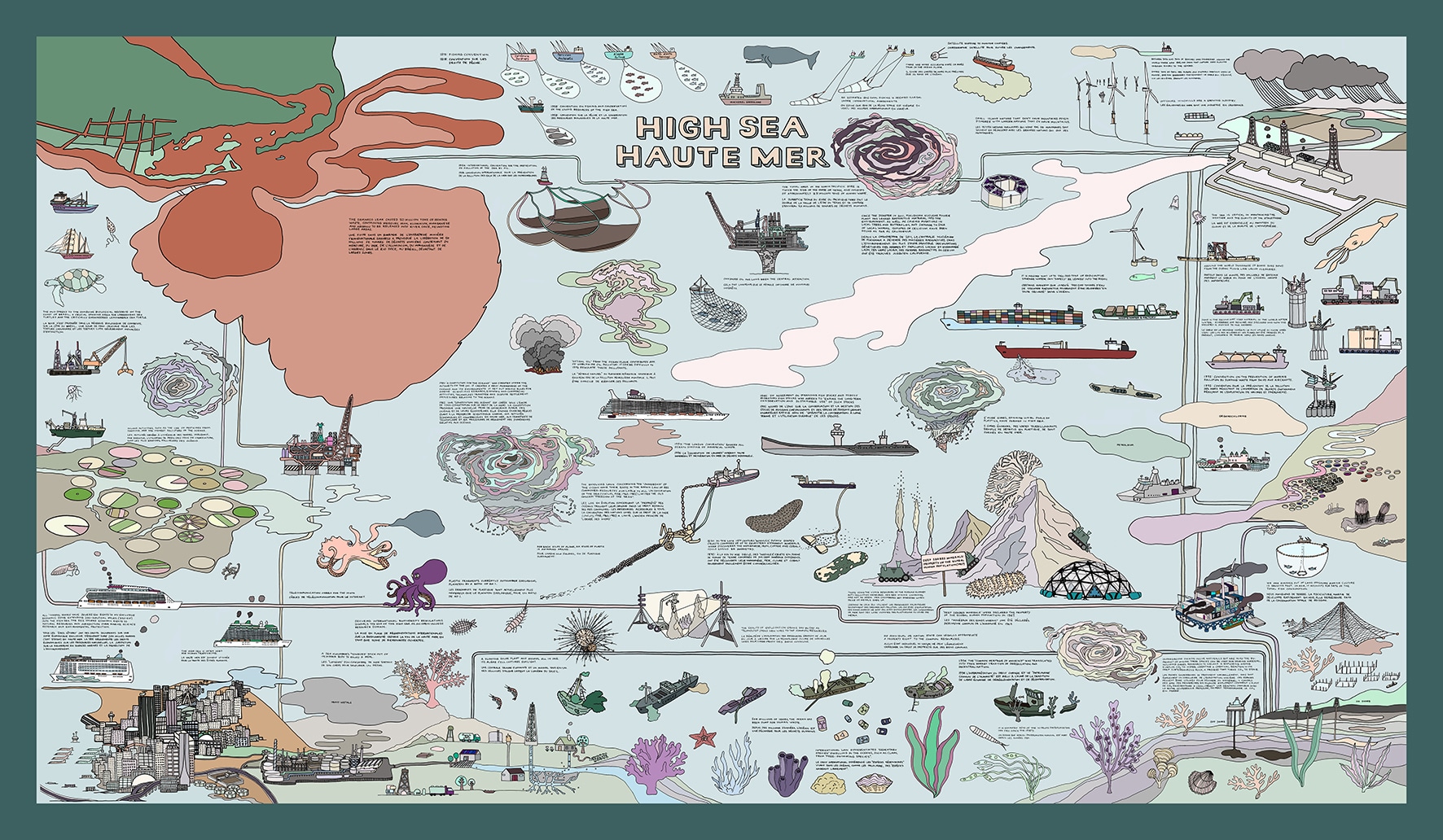

Rikke Luther also explores the complexities of the environ- mental crisis but does so by tying multiple layers together at a larger scale, connecting language, politics, financialization, law, biology and the economy. The complex relationship between contamination and politics is crucial to Jessika Khazrik for The Society of False Witnesses as she questions in detail the role of ecology in the formation of nation states, both historically and in the present. Inspired by the diaries of an Egyptian oceanographer who in the 1930s was part of a British scientific exhibition to the Red Sea, which is now battling heavy pollution, Marianne Fahmy brings to the fore the complex interrelationships between scientific research and exploration, nationalism and political identity.

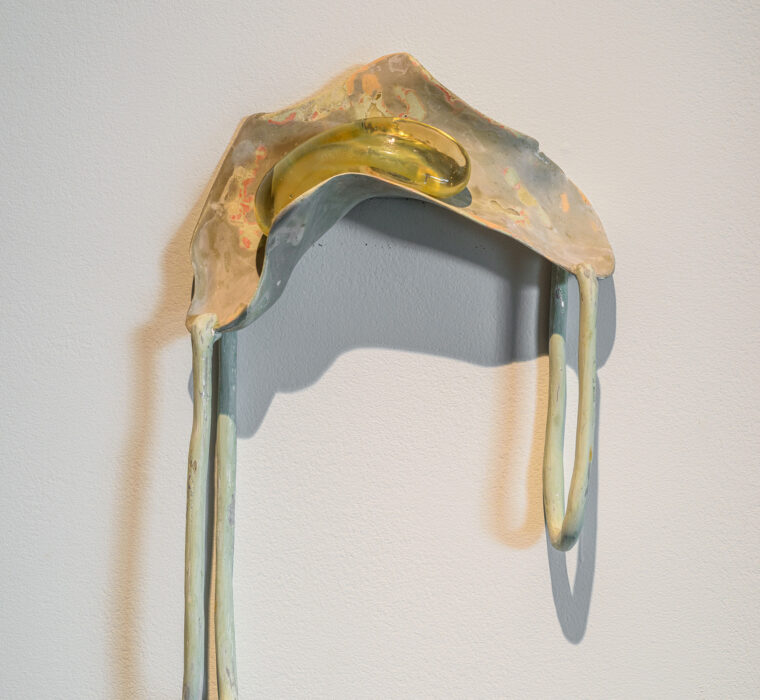

Diving into the fragile ecosystem within which we live and seeing the pernicious contamination of those substances that we depend upon for life (such as water, food and air), we are pressed to consider if it is possible to decontaminate and practice degrowth – and if so, how. Could healing follow the same routes that contamination has travelled? There is not a parcel of land or group of living organisms that seems to escape toxicity, or at least this is what Anouk Kruithof’s aerial photographs of oil spills and chemical waste dumps seem to suggest. Her soft, prosthesis-like sculptures play with the idea of protection versus contamination. Daisy Lafarge also ponders the possibility of immunity to noxious environments. Can we reasonably ‘wait quietly for the rains’ to wash away the poison or for some miracle to cure us?

Elvia Teotski addresses ecological vulnerability and toxic imprints in the region of Marseilles. Collecting and sampling substrates, deposits, particulate water, she examines invisible yet hazardous pollution and the impossibility of upcycling it. Minia Biabiany brings another localized scandal to the fore, focusing on chlordecone, an insecticide with severe polluting effects on land, phreatic tables, the food chain and bodies that was widely applied in banana fields in Guadeloupe and Martinique between the 1970s and 1993. This case, as well as the pollution of Marseilles, are scrutinized in posters printed from the book Atlas de la France Toxique, a compilation of maps of different types of pollution in France made by the environmental association Robin des Bois. As early as 1946, the poet René Char raised his voice against the contamination of waterways in Provence with his theatre play Le Soleil des eaux. Spectacle pour une toile de pêcheurs. As for Lisa Robertson’s poem Rivers, it connects the many bodies that share riverine environments, exposing their collective vulnerability to toxins, hormones and desire.

In reaction to the release of sewage into waterways by factories such as those involved in the textile industry, Valentina Karga works with natural dyes, emphasizing the importance of alternatives to toxic production processes that in their current form infect the environment. Marjolijn Dijkman & Toril Johannessen make us further aware of the effects of climate change by filming microorganisms, through a microscope, in samples of brackish water taken from the inner Oslo Fjord, where traces of human activity can be seen in altered saline and sea levels, among other phenomena.

Rikke Luther also explores the complexities of the environ- mental crisis but does so by tying multiple layers together at a larger scale, connecting language, politics, financialization, law, biology and the economy. The complex relationship between contamination and politics is crucial to Jessika Khazrik for The Society of False Witnesses as she questions in detail the role of ecology in the formation of nation states, both historically and in the present. Inspired by the diaries of an Egyptian oceanographer who in the 1930s was part of a British scientific exhibition to the Red Sea, which is now battling heavy pollution, Marianne Fahmy brings to the fore the complex interrelationships between scientific research and exploration, nationalism and political identity.

Diving into the fragile ecosystem within which we live and seeing the pernicious contamination of those substances that we depend upon for life (such as water, food and air), we are pressed to consider if it is possible to decontaminate and practice degrowth – and if so, how. Could healing follow the same routes that contamination has travelled? There is not a parcel of land or group of living organisms that seems to escape toxicity, or at least this is what Anouk Kruithof’s aerial photographs of oil spills and chemical waste dumps seem to suggest. Her soft, prosthesis-like sculptures play with the idea of protection versus contamination. Daisy Lafarge also ponders the possibility of immunity to noxious environments. Can we reasonably ‘wait quietly for the rains’ to wash away the poison or for some miracle to cure us?

CCN Ballet National de Marseille – direction (LA)HORDE, Marseilles, France

September 10 – October 25, 2020

Opening hours

Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays: 14.00–19.00

Wednesdays: 10.00–14.00

Closed on Saturdays and Sundays.

Free admission.

Special openings

Saturday, September 12 14.00 – 18.00

The evenings of September 18 & 19 in the framework of the immersive sound and visual installation ORLANDO presented by the gmem; and the evenings of October 1 & 2 and October 9, 2020.

Manifesta 13 Les Parallèles du Sud received the support of Région Sud. The exhibition received the kind and generous contributions of the Danish Arts Foundation, the Dutch Embassy in Paris, the École Nationale de Danse de Marseille, the Galerie Valeria Cetraro, Mondriaan Fund, Office for Contemporary Art Norway (OCA), the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Paris and the State Culture Capital Foundation of Latvia; and received propitious support by publishers Arthaud, Gallimard, Coach House Books, Sad Press and the association Robin des Bois. It was also part of the Saison VIVANT2020.

CCN Ballet National de Marseille – direction (LA)HORDE, Marseilles, France

September 10 – October 25, 2020

Opening hours

Mondays, Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays: 14.00–19.00

Wednesdays: 10.00–14.00

Closed on Saturdays and Sundays.

Free admission.

Special openings

Saturday, September 12 14.00 – 18.00

The evenings of September 18 & 19 in the framework of the immersive sound and visual installation ORLANDO presented by the gmem; and the evenings of October 1 & 2 and October 9, 2020.

Manifesta 13 Les Parallèles du Sud received the support of Région Sud. The exhibition received the kind and generous contributions of the Danish Arts Foundation, the Dutch Embassy in Paris, the École Nationale de Danse de Marseille, the Galerie Valeria Cetraro, Mondriaan Fund, Office for Contemporary Art Norway (OCA), the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Paris and the State Culture Capital Foundation of Latvia; and received propitious support by publishers Arthaud, Gallimard, Coach House Books, Sad Press and the association Robin des Bois. It was also part of the Saison VIVANT2020.

Talk

Elvia Teotski did a lecture performance during the opening of the exhibition on September 10. She shared more about her research process in the framework of the commission we made to her to work on the red sludge in Marseilles and its region:

« Disséminée,

Les collines se forment,

Aujourd’hui elles donnent du relief à notre territoire urbain.

Crassier de la Barasse Montgrand, crassier de la Barasse Saint-Cyr,

crassier Saint Louis ..

Coincé entre une voie ferrée et l’Huveaune, entre un centre de tri et les Aygalades, Ou recouvert de terre et revégétalisé.

Zone d’éco-patûrage ou aire de pique-nique. »

Talk

Elvia Teotski did a lecture performance during the opening of the exhibition on September 10. She shared more about her research process in the framework of the commission we made to her to work on the red sludge in Marseilles and its region:

« Disséminée,

Les collines se forment,

Aujourd’hui elles donnent du relief à notre territoire urbain.

Crassier de la Barasse Montgrand, crassier de la Barasse Saint-Cyr,

crassier Saint Louis ..

Coincé entre une voie ferrée et l’Huveaune, entre un centre de tri et les Aygalades, Ou recouvert de terre et revégétalisé.

Zone d’éco-patûrage ou aire de pique-nique. »

Mediation

We were lucky to collaborate with mediator Elsa Roussel who did an amazing work disseminating the exhibition to the public. We particularly worked strongly towards the public of students of the ENDM (École Nationale de Danse de Marseille).

Podcast

On October 25, I discussed the exhibition and topics of pollution, circulation and toxicity in Marseilles with Geoffroy Mathieu, photographer presenting his series La mauvaise réputation, and Pierre Revel, from the association Rives & Culture presenting the project Collines en ville.

Podcast

On October 25, I discussed the exhibition and topics of pollution, circulation and toxicity in Marseilles with Geoffroy Mathieu, photographer presenting his series La mauvaise réputation, and Pierre Revel, from the association Rives & Culture presenting the project Collines en ville.

Collaboration

Thanks to TBA-21, Spoiled Waters Spilled has navigated the virtual space of the Ocean Archive where we have shared insights into the work and research of some of the exhibition’s artists, a podcast of conversations with the artists and videos available for the duration of the exhibition.

TBA-21 is an art foundation focussing on art, research and climate change founded in 2002 by Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza in Vienna.

Ocean Archive is designed to be a pedagogical, research and storytelling tool for a broad audience, which translates current knowledge about the Ocean into shared language that enables us to make better decisions for urgently needed policies.

Collaboration

Thanks to TBA-21, Spoiled Waters Spilled has navigated the virtual space of the Ocean Archive where we have shared insights into the work and research of some of the exhibition’s artists, a podcast of conversations with the artists and videos available for the duration of the exhibition.

TBA-21 is an art foundation focussing on art, research and climate change founded in 2002 by Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza in Vienna.

Ocean Archive is designed to be a pedagogical, research and storytelling tool for a broad audience, which translates current knowledge about the Ocean into shared language that enables us to make better decisions for urgently needed policies.

Press

Elle Provence, C’est Manifesta !, September 18, 2020