Ground Control

[Markkontroll]

Artists

Maria Thereza Alves

Gerd Aurell

Hanan Benammar

Céline Condorelli

Suzanne Husky

Mónica de Miranda

Ground Control

[Markkontroll]

Artists

Maria Thereza Alves

Gerd Aurell

Hanan Benammar

Céline Condorelli

Suzanne Husky

Mónica de Miranda

The exhibition Ground Control explores issues in the intersection of botany, politics and history. By exploring the circulation routes of plants, in the framework of botanical politics, we have put together the exhibition Ground Control in an attempt to shift the perception of what is local and natural, and that might actually be imported and constructed. It entices us to reconsider our surroundings beyond borders and understand their political entrenchment. As opposed to ideas of a ‘pure’ and uncontaminated vegetation, the artworks presented explore plants as witnesses and cultural imports, reflecting the continuous fluxes, frictions and permeations that shape our political, economic and natural environments. The artworks also emphasize visible and invisible imprints left locally on flora, language, knowledge and bodies affected by such circulation.

The exhibition Ground Control explores issues in the intersection of botany, politics and history. By exploring the circulation routes of plants, in the framework of botanical politics, we have put together the exhibition Ground Control in an attempt to shift the perception of what is local and natural, and that might actually be imported and constructed. It entices us to reconsider our surroundings beyond borders and understand their political entrenchment. As opposed to ideas of a ‘pure’ and uncontaminated vegetation, the artworks presented explore plants as witnesses and cultural imports, reflecting the continuous fluxes, frictions and permeations that shape our political, economic and natural environments. The artworks also emphasize visible and invisible imprints left locally on flora, language, knowledge and bodies affected by such circulation.

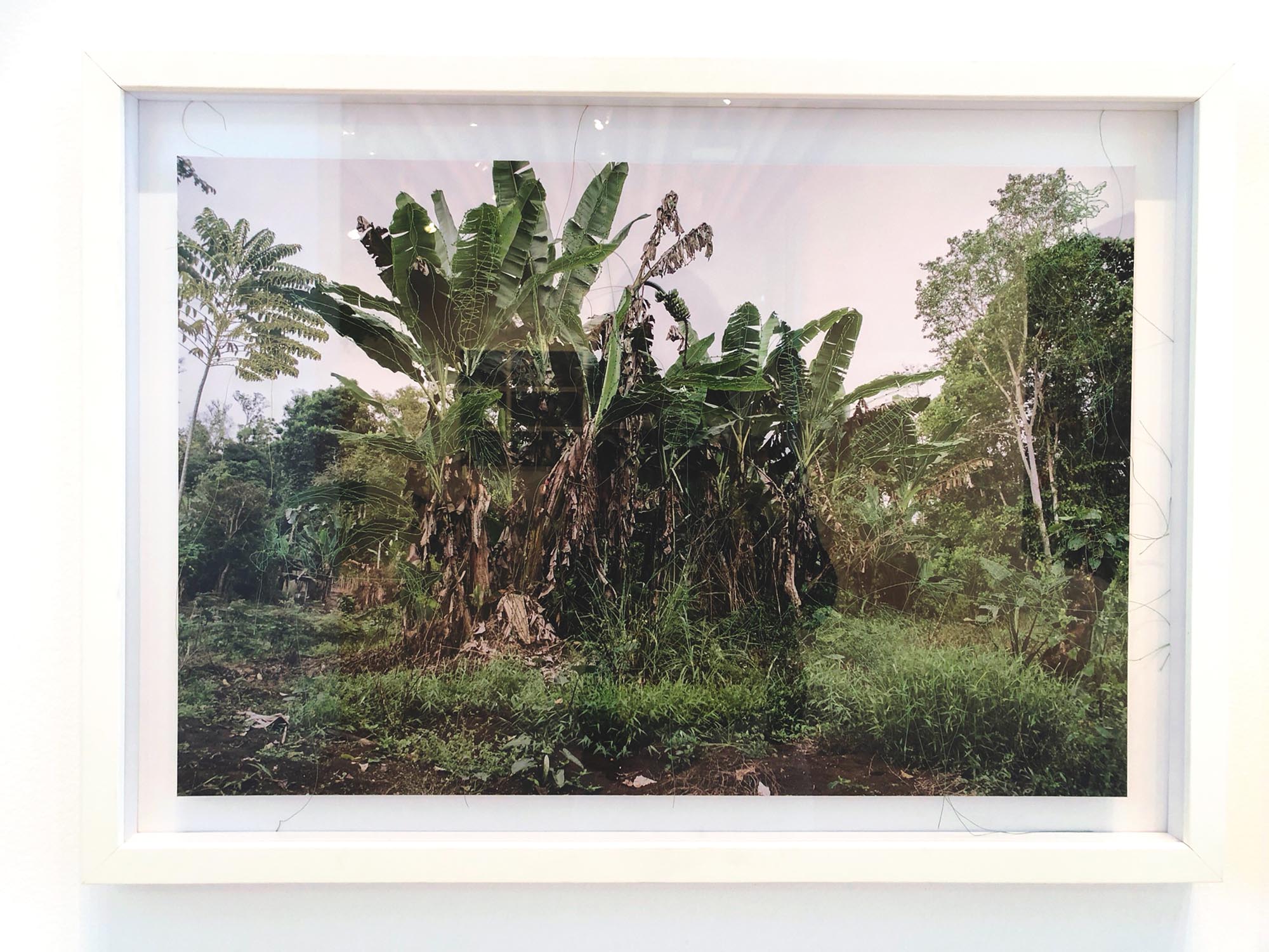

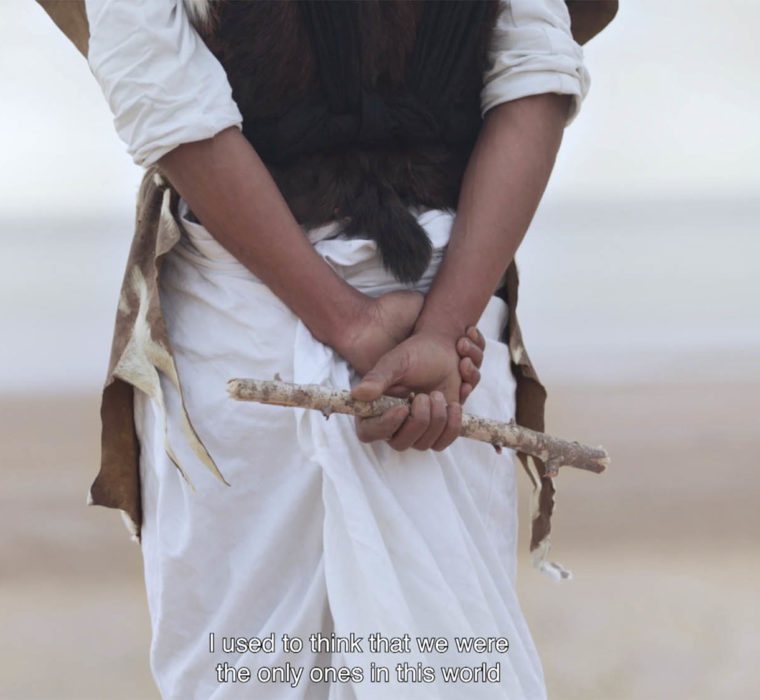

Plants’ connection to world politics may be exemplified in the history of colonialism. The development of naturalist expeditions were intimately connected to the Western imperial conquest and competition in the 16th–18th centuries. The documentation of plants and mapping of territories subsequently led to their occupation and plundering. Botanical gardens had a number of functions in this context. They were hierarchical spaces in which plants from all over the world were labelled, categorised and admired. In the Empires and in their colonies, botanical gardens became strategic power markers, as well as trade opportunities. During the era of imperial competition, plants were transferred from one environment to another, often transiting through or staying in ‘acclimatisation’ gardens, permanently modifying, sometimes unpredictably, both ecosystems and systems of meanings. In the exhibition, nature as witness to a history of colonization and one of its present day consequences – the fact that many people are living their lives in diaspora, is portrayed by artist Mónica de Miranda in her photographs.

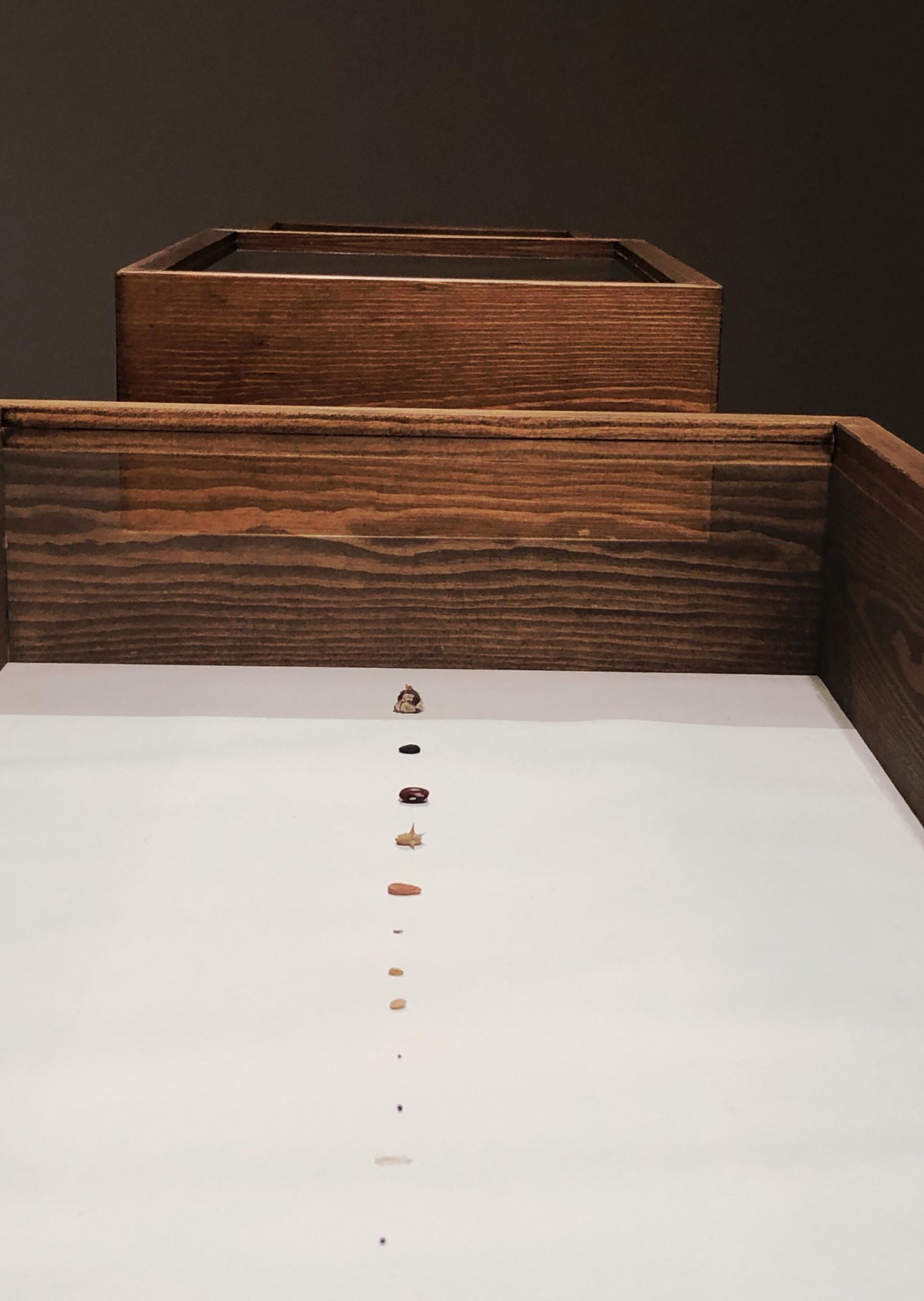

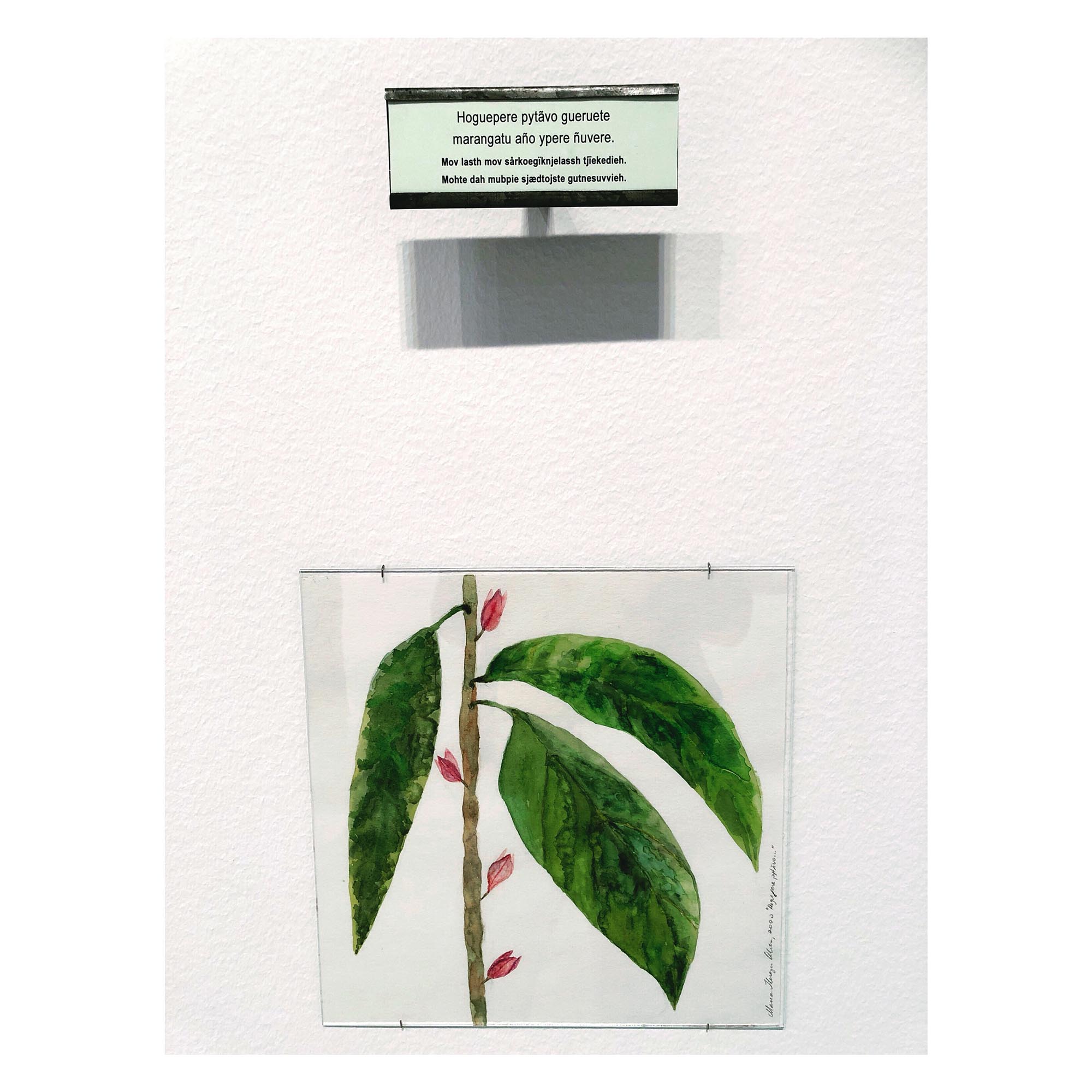

The application of classification and taxonomy brought further consequences. Old names and knowledge were wiped out and flora became objectified – removed from its original context and displayed in greenhouses, vitrines, cabinets and collections as rarities to be scientifically studied or merely enjoyed, rather than as living agents integrated into people’s routines because of their nutritional, medical, spiritual or magical qualities. Binominal nomenclature represents a will to hierarchize and classify not only nature, but also animals, and sadly humans. The new system of Carl von Linné – the binomial nomenclature – eventually became the norm and represented a knowledge valued as encyclopaedic and total, but which mainly one of its present day consequences – the fact that many people are living their lives in diaspora, oral, ancestral and intuitive knowledge. This resulted in a considerable subsequent loss of indigenous plant knowledge, as highlighted in the exhibition by the artworks of artists Hanan Benammar and Maria Thereza Alves. Several pressing questions emerge: What knowledge is valuable for us today? Is it possible to reactivate or reappropriate the names, usages and teachings of language and plants?

Plants’ connection to world politics may be exemplified in the history of colonialism. The development of naturalist expeditions were intimately connected to the Western imperial conquest and competition in the 16th–18th centuries. The documentation of plants and mapping of territories subsequently led to their occupation and plundering. Botanical gardens had a number of functions in this context. They were hierarchical spaces in which plants from all over the world were labelled, categorised and admired. In the Empires and in their colonies, botanical gardens became strategic power markers, as well as trade opportunities. During the era of imperial competition, plants were transferred from one environment to another, often transiting through or staying in ‘acclimatisation’ gardens, permanently modifying, sometimes unpredictably, both ecosystems and systems of meanings. In the exhibition, nature as witness to a history of colonization and one of its present day consequences – the fact that many people are living their lives in diaspora, is portrayed by artist Mónica de Miranda in her photographs.

The application of classification and taxonomy brought further consequences. Old names and knowledge were wiped out and flora became objectified – removed from its original context and displayed in greenhouses, vitrines, cabinets and collections as rarities to be scientifically studied or merely enjoyed, rather than as living agents integrated into people’s routines because of their nutritional, medical, spiritual or magical qualities. Binominal nomenclature represents a will to hierarchize and classify not only nature, but also animals, and sadly humans. The new system of Carl von Linné – the binomial nomenclature – eventually became the norm and represented a knowledge valued as encyclopaedic and total, but which mainly one of its present day consequences – the fact that many people are living their lives in diaspora, oral, ancestral and intuitive knowledge. This resulted in a considerable subsequent loss of indigenous plant knowledge, as highlighted in the exhibition by the artworks of artists Hanan Benammar and Maria Thereza Alves. Several pressing questions emerge: What knowledge is valuable for us today? Is it possible to reactivate or reappropriate the names, usages and teachings of language and plants?

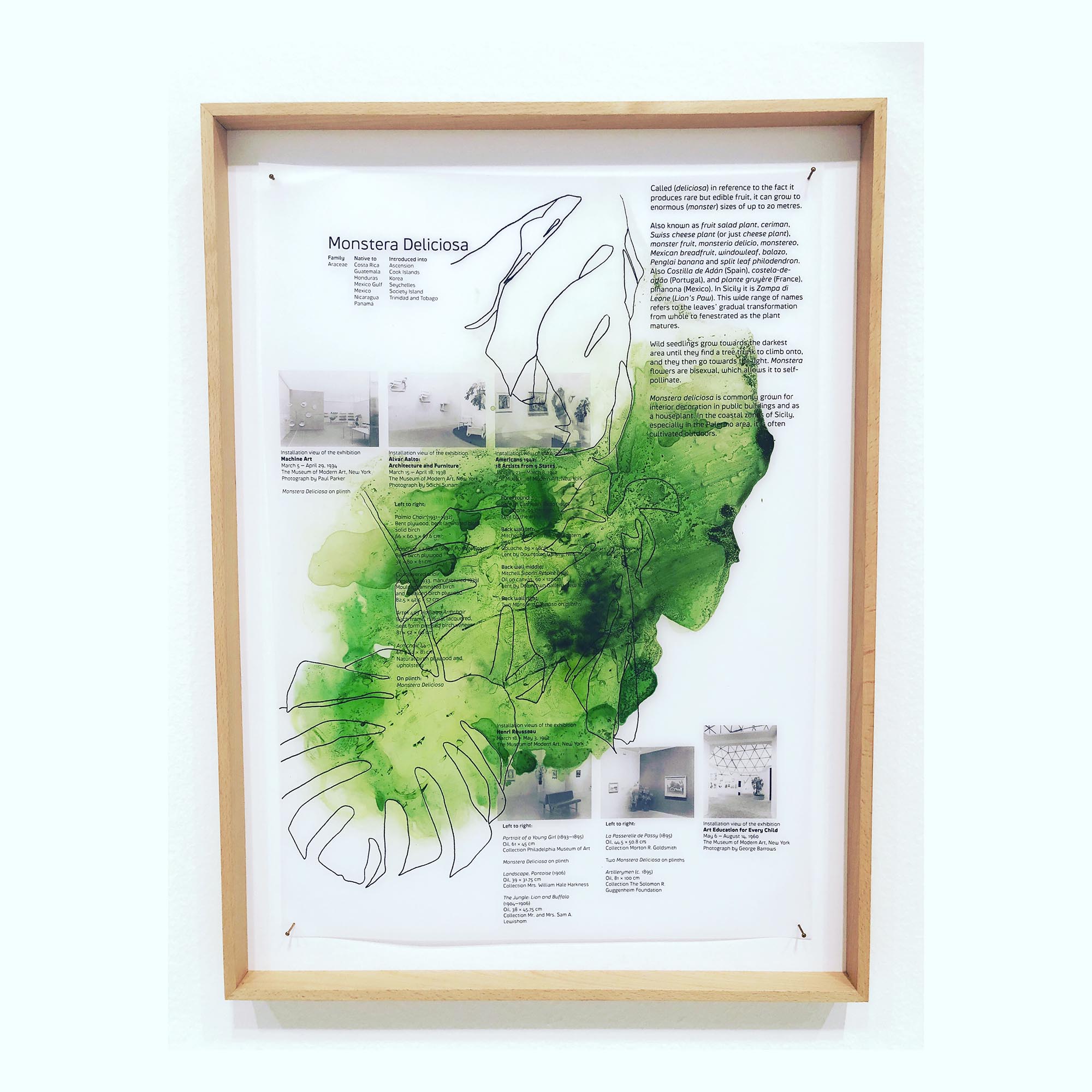

Ground Control also focuses on the circulation of plants in the world from the perspective of their commodification, as both desirable ornamental elements for individuals and institutions and as profitable resources for corporations. The increased availability of plants contributed to their use in domestic and public spaces, particularly exotic and tropical species, which signalled social prestige and became choice gifts and adornments for parlours. The exhibition presents Céline Condorelli’s series of Plant study prints that document the histories and qualities of some regular house plants that were formerly used to furnish art exhibitions up until the 1970s and are still commonly found in homes and offices. Retracing the history of display and ornamentation – the passage of nature from outdoor to indoor as house plants – suggests that the original significations and usages of plants were further suppressed during this domestication process.

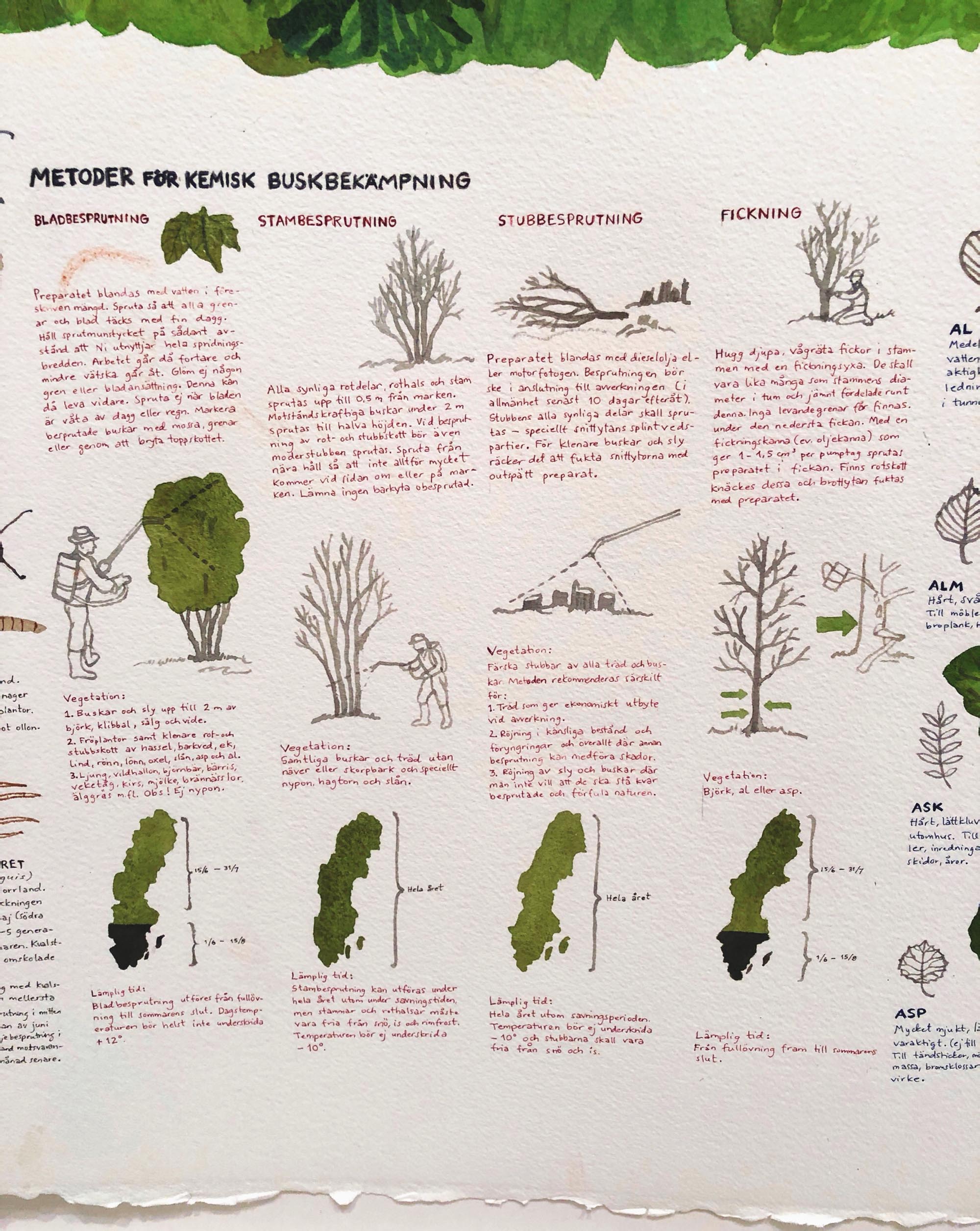

Flora made its entrance with great pomp in trade circuits, leading to the development of the horticulture industry we know today. Gerd Aurell’s artworks in the exhibition are the result of her research about how the Swedish forestry industry developed during the 20th century – including massive clear-cuts and widespread use of the herbicide hormoslyr – which in hindsight proved to cause both major biodiversity loss in forests and disease among forest rangers and locals. In some cases, the current interest in nature’s economic potential has generated unholy alliances between politics, public authorities and businesses to the detriment of the environment, on many occasions demonstrating the supremacy of capitalism over ecological needs. Artists such as Suzanne Husky consistently remind us that we are all connected to Mother Earth and that the exploitation of land also comes at a price; there is a risk of losing what we hold sacred, and a risk of losing knowledge tied to a particular territory. Sadly, the exploitation of nature is often accompanied by pollution, destruction and disruption of the balance of ecosystems. Against this background, we find it encouraging to engage with artists highlighting regenerative practices and activism to protect our common resources.

Ground Control also focuses on the circulation of plants in the world from the perspective of their commodification, as both desirable ornamental elements for individuals and institutions and as profitable resources for corporations. The increased availability of plants contributed to their use in domestic and public spaces, particularly exotic and tropical species, which signalled social prestige and became choice gifts and adornments for parlours. The exhibition presents Céline Condorelli’s series of Plant study prints that document the histories and qualities of some regular house plants that were formerly used to furnish art exhibitions up until the 1970s and are still commonly found in homes and offices. Retracing the history of display and ornamentation – the passage of nature from outdoor to indoor as house plants – suggests that the original significations and usages of plants were further suppressed during this domestication process.

Flora made its entrance with great pomp in trade circuits, leading to the development of the horticulture industry we know today. Gerd Aurell’s artworks in the exhibition are the result of her research about how the Swedish forestry industry developed during the 20th century – including massive clear-cuts and widespread use of the herbicide hormoslyr – which in hindsight proved to cause both major biodiversity loss in forests and disease among forest rangers and locals. In some cases, the current interest in nature’s economic potential has generated unholy alliances between politics, public authorities and businesses to the detriment of the environment, on many occasions demonstrating the supremacy of capitalism over ecological needs. Artists such as Suzanne Husky consistently remind us that we are all connected to Mother Earth and that the exploitation of land also comes at a price; there is a risk of losing what we hold sacred, and a risk of losing knowledge tied to a particular territory. Sadly, the exploitation of nature is often accompanied by pollution, destruction and disruption of the balance of ecosystems. Against this background, we find it encouraging to engage with artists highlighting regenerative practices and activism to protect our common resources.

Bildmuseet, Umeå, Sweden

September 27, 2020 – April 11, 2021

Sound Excerpts

Maria Thereza Alves, Introduction to Decolonizing Botany, 2020

In Ground Control, the artist presents three works from her new series. She shows three watercolours and three botanical signs, each accompanied by a plant honouring song sung by a member of the Guarani people from the Jaguapiru Reserve in Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Here is an excerpt:

Maria Thereza Alves, Orée, 2011

Excerpt from the video Orée shot in La Réunion in which two actors pronounce the Creole names for some of the island’s endemic plants, revealing their close history with marronnage, and the very different status and value attributed to free white women versus enslaved black women in Réunion’s history:

Sound Excerpts

Maria Thereza Alves, Introduction to Decolonizing Botany, 2020

In Ground Control, the artist presents three works from her new series. She shows three watercolours and three botanical signs, each accompanied by a plant honouring song sung by a member of the Guarani people from the Jaguapiru Reserve in Dourados, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Here is an excerpt:

Maria Thereza Alves, Orée, 2011

Excerpt from the video Orée shot in La Réunion in which two actors pronounce the Creole names for some of the island’s endemic plants, revealing their close history with marronnage, and the very different status and value attributed to free white women versus enslaved black women in Réunion’s history:

Performance

The first week-ends of the exhibition, Sofia Aurell performed Svenska växter, a piece from Gerd Aurell in 1995. All of the plants from a Swedish botanical book are drawn on a piece of wall, one species on top of the other, until they merge into one single shape. The artist’s intention is to free the plants from the book’s Linnaean structure and organised way of viewing nature, returning them to chaos.

Performance

The first week-ends of the exhibition, Sofia Aurell performed Svenska växter, a piece from Gerd Aurell in 1995. All of the plants from a Swedish botanical book are drawn on a piece of wall, one species on top of the other, until they merge into one single shape. The artist’s intention is to free the plants from the book’s Linnaean structure and organised way of viewing nature, returning them to chaos.

Quotes

We have asked all the artists in the exhibition to share a note about their relation to botanical politics and references that are crucial for them.

‘My interest in botanical studies became ethnobotanical, or the relationship between plants and humans. This relationship quickly brought me to the history of migration and settlements, colonization, land grabbing and neo-colonization, as well as a long history of resilience, raising questions about the materialization of knowledge and forms of knowledge transmission.’

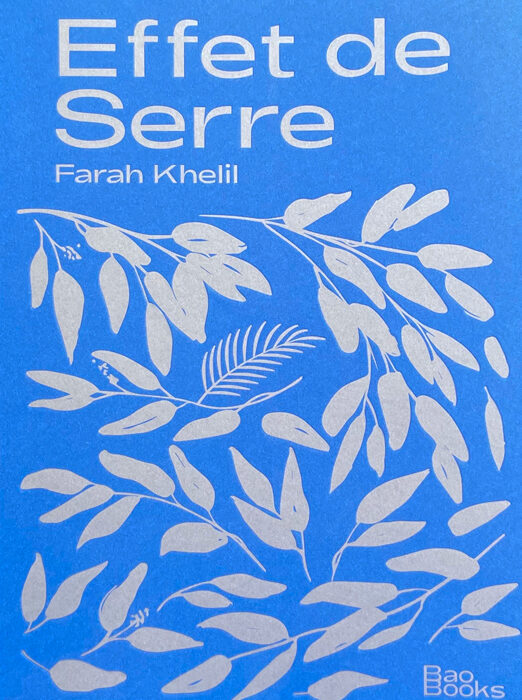

— Hanan Benammar

‘The botanic garden, a non-place recreated with artificial borders as a product of pleasure and leisure, is associated with the colonial idea of ‘collecting’ and ‘inventorying’ the globe. Its exuberance and exhaustiveness offered an image of the power of Empires and a ‘controllable chaos’ that opposed the bucolic order of the natural landscape of European agricultural production lands. The indefinable nature of botanic gardens has made them points of cultural exchange and preferred places for the projection of myths, utopias, dystopias, arcades and Eden.’

— Mónica de Miranda

Talk

On October 18, 2020, Céline Condorelli talks about her project Zanzibar and politics of display.

On November 8, 2020, Maria Thereza Alves presents her new work Decolonizing Botany, and shares about how her work is inspired by the article Decolonization is not a metaphor by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang.

All events are live streamed.

Quotes

We have asked all the artists in the exhibition to share a note about their relation to botanical politics and references that are crucial for them.

‘My interest in botanical studies became ethnobotanical, or the relationship between plants and humans. This relationship quickly brought me to the history of migration and settlements, colonization, land grabbing and neo-colonization, as well as a long history of resilience, raising questions about the materialization of knowledge and forms of knowledge transmission.’

— Hanan Benammar

Talk

On October 18, 2020, Céline Condorelli talks about her project Zanzibar and politics of display.

On November 8, 2020, Maria Thereza Alves presents her new work Decolonizing Botany, and shares about how her work is inspired by the article Decolonization is not a metaphor by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang.

All events are live streamed.

‘The botanic garden, a non-place recreated with artificial borders as a product of pleasure and leisure, is associated with the colonial idea of ‘collecting’ and ‘inventorying’ the globe. Its exuberance and exhaustiveness offered an image of the power of Empires and a ‘controllable chaos’ that opposed the bucolic order of the natural landscape of European agricultural production lands. The indefinable nature of botanic gardens has made them points of cultural exchange and preferred places for the projection of myths, utopias, dystopias, arcades and Eden.’

— Mónica de Miranda